Extreme Eviction: Removing Andy Smith

After WW II, tens of thousands of federal employees settled in rural Fairfax County. Anne Wilkins, a member of the Board of Supervisors, hoped improvements in “municipal services” would follow the influx of these “newcomers” along with welcome political challenges to the “Old Virginians.” Wilkins did not like “large landowners” who scorned the middle-class professional and “taxpayer” who sought to build a suburb outside Washington, DC.[1] Despite the growth in population and development, Fairfax still had blighted areas, where deserted properties sat idle. The Board of Supervisors fretted about these abandoned plots and wondered whether the Alexandria Housing Authority’s effort in 1939 to “eliminate…[u]nsanitary conditions” could provide a model to emulate.[2] In the early 1960s, the Fairfax Public Health Department and auxiliary Division of Environmental Health started to enforce the newly passed housing hygiene codes. Around that time the county enacted an ordinance giving broad (interventionist) powers to the Public Health Department and its seventeen sanitarians who were supervised by a director, Dr. Harold Kennedy, and his two assistant directors.[3]

The Washington Post covered the incipient work of the Division of Environmental Health. Under the headline “Fairfax Unit Cracks Down,” an article chronicled the demolition of dwellings “unfit for human habitation.”[4] Leading the effort was Dr. Harold Kennedy, who reported the destruction of 767 separate locations; “559 involved white families and 208, Negro.” His intention was to raze “those houses in extreme dilapidation” and move “migrants” from neglected sites that reputedly posed “fire, safety and health hazards.”[5] Dr. Kennedy estimated the number of derelict homes countywide: 4000, “of which at least 500 were vacant.”[6]

Property developers advocated for even stricter and faster implementation of eviction orders to clear the “pockets” of “rude huts which were there long before suburbia consumed the areas around them.”[7] While newspapers generally endorsed the purpose behind this action, they expressed a cautious attitude because Black people in “the oldest slums . . . could not be touched” due to the “limitations of eviction laws.”[8] The Fairfax African American community of Gum Springs was frequently cited in the press as a place “of crowded shacks . . . poor or nonexistent drainage and sewage,” which if leveled could create environmental problems and social unrest.[9] Between 1963 and 1966, Dr. Kennedy's focused interventions in impoverished Black areas led to a crisis of “homeless[ness].” Worried about this dire situation, Fairfax Board of County Supervisors passed an “emergency amendment” providing an automatic review of removal “orders issued by the health department.”[10] The measure read like a stay of execution.

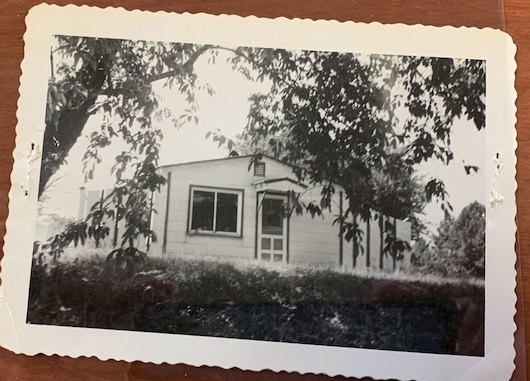

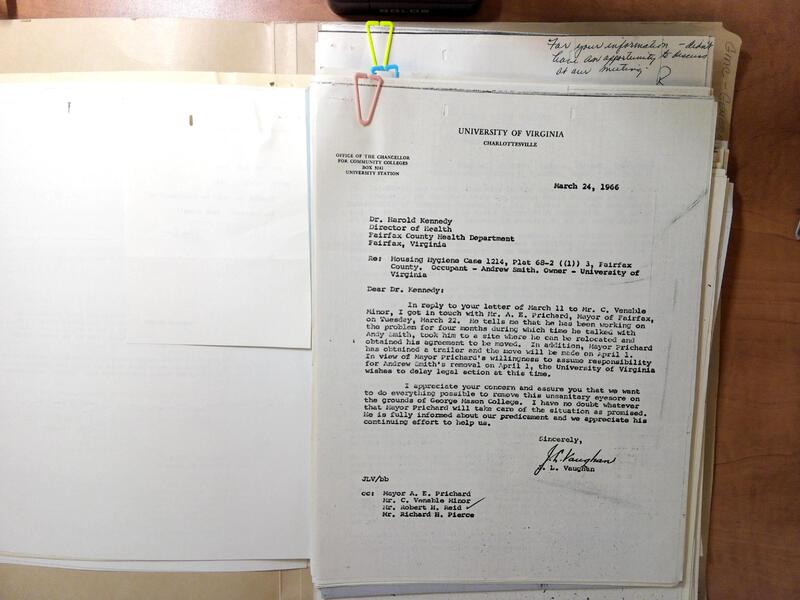

Meanwhile, one site close to George Mason College (GMC) on Ox Road (Route 123) became a pressing concern of health and hygiene activists. Andy Smith was living in a trailer at this location, as he had for many years. During a January 1965 GMC Advisory Committee meeting administrators discussed the presence of a “squatter” in their midst. They wanted him gone and stated as much to colleagues at the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville.[11] The UVA Chancellor for Community Colleges, J.L. Vaughan, then wrote Dr. Kennedy, copying GMC associates and Mayor Prichard of the Town of Fairfax. Vaughan told Kennedy that Prichard “had been working . . . for four months” to convince Andy Smith to relocate to another spot and finally “obtained his agreement to be moved.” Because Smith apparently consented to his “removal on April 1, the University of Virginia” agreed “to delay legal action.” The trailer and its occupant were also described in writing as “this unsanitary eyesore on the grounds of George Mason College.”[12]

Andy Smith’s next dwelling was selected. It was another trailer, and a used one at that. The structure had been purchased by unnamed community members who liked that he waved to cars driving on Route 123. In 1967 Smith packed up his belongings and headed to his new domestic destination: Fairfax City’s Sewage Treatment Plant. There, Andy Smith was supposed to reside “rent-free, with free water and sewer facilities for the rest of his life.”[13] The actual cost to Fairfax City of funding Andy Smith’s presence on toxic municipal land amounted to $30 per month. Smith’s Sewage Treatment Plant arrangement enabled him to watch little league baseball at an adjacent park, where he directed traffic on game days. When Andy Smith’s trailer was wrecked by Hurricane Agnes in 1972, his unnamed community friends stepped in again, raising approximately $1,000 to replace his ruined dwelling and soaked furnishings. Eight years later Fairfax City decided to dislodge Andy Smith a second time. When informed of this decision, Andy allegedly replied, “I ain’t moving,” before qualifying his sentiment with words of protest: the authorities “moved me…into this hole” with a promise of “lifetime” security.[14] The story circulated; controversy ensued. The plan to remove Andy Smith was scrubbed in the spring of 1975. City Mayor Nathaniel Young was contacted by the Washington Post and asked about the persistently “paternalistic treatment” of Andy Smith. On April 14, 1975, the paper ran an article titled, “What to Do with Andy Smith? He Doesn’t Want to Move?” The reporter quoted Mayor Young’s reflections on Smith’s struggle to keep his home and why Fairfax went back on its plans. Young said he extended “a gesture to help . . . [this] fellow man . . . who has been friendly to everyone.”[15] Andy Smith managed to remain at the Sewage Treatment Plant site for the rest of his days until he passed away on 13 July 1978.

By George Oberle

[1] Anne Wilkins, “Fairfax Progress,” The Washington Post, March 31, 1955, 14. For different interpretation of this letter, see: Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 2020), 27. Scholarship examining the form of suburbanization that shaped Fairfax: Robert Beauregard, How America Became Suburban (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), ix-xiv, 1-16; Paige Glotzer, How the Suburbs Were Segregated: Developers and the Business of Exclusionary Housing, 1890-1960 (New York: Columbia University, 2020).

[2] Krystyn R. Moon, “The African American Housing Crisis in Alexandria, Virginia, 1930s-1960s,” Virginia Magazine of History & Biography 124, no. 1 (January 2016), 38.

[3] County of Fairfax, “Annual Report,” 1965 (Fairfax: VA, 1965), 20-21; County of Fairfax, “Annual Report,” 1965 (Fairfax: VA, 1965), 22-24.

[4] “Fairfax Unit Cracks Down on Housing,” The Washington Post, September 10, 1963.

[5] “Fairfax Unit Cracks Down on Housing,” The Washington Post, September 10, 1963.

[6] “Fairfax Unit Cracks Down on Housing,” The Washington Post, September 10, 1963.

[7] William Chapman, “Suburban Counties Are Learning They Have Slum Pockets: 1000 Substandard,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), March 5, 1961, sec. B1.

[8] William Chapman, “Suburban Counties Are Learning They Have Slum Pockets: 1000 Substandard,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), March 5, 1961, sec. B1. A white citizens group also began to advocate “for a housing ordinance” that could remove the “‘shocking’ and ‘appalling’ conditions . . . found” in parts of Fairfax.

[9] William Chapman, “Fairfax Code For Clearing Slums Due: Flooding and Overcrowding,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), October 30, 1960, B1.

[10] Hank Burchard, “Fairfax Slum Dwellers Get Word: They Have Reprieve, Help on Way: Help on Way For Fairfax Slum Areas,” The Washington Post, May 19, 1966, D1.

[11] Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes, 19 January 1965, John C. Wood papers, Collection #C0115, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[12] Letter J.L. Vaughan to Dr. Harold Kennedy, 24 March 1966. Box 1, folder 4, John C. Wood papers, Collection #C0115, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries. This case contradicts the account in William Page Johnson II, “Andrew B. ‘Andy’ Smith: A Legacy in a Gesture,” The Fare Facs Gazette: The Newsletter of Historic Fairfax City Inc., Vol. n. 3, Summer 2018, 8.

[13] William Page Johnson II, “Andrew B. ‘Andy’ Smith: A Legacy in a Gesture,” The Fare Facs Gazette: The Newsletter of Historic Fairfax City Inc., Vol. n. 3, Summer 2018, 9.

[14] Douglas C. Lyons, “What to Do with Andy Smith?: He Doesn’t Want to Move,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), April 14, 1975, C-1.

[15] Douglas C. Lyons, “What to Do with Andy Smith?: He Doesn’t Want to Move,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), April 14, 1975, C-1.