Colonial and Antebellum Alexandria

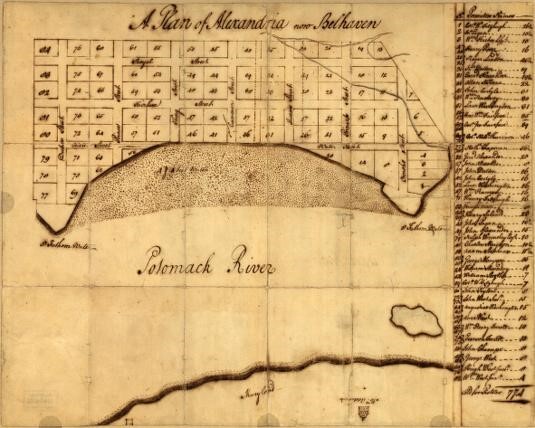

Alexandria was founded in 1749 by a group of Scottish merchants. The city is eponymous of the original landowner and friend, John Alexander. Alexandria is considered George Washington’s adopted home because he surveyed it, attended church there, resided nearby, and had both a townhome and rental properties in town.[1]

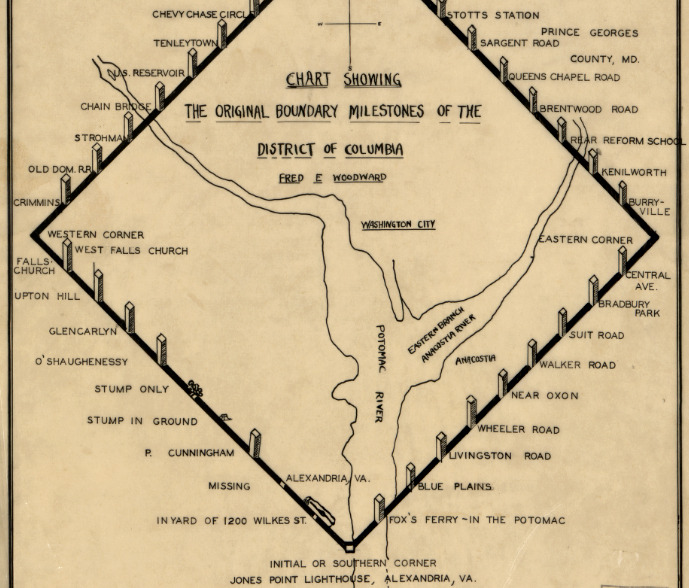

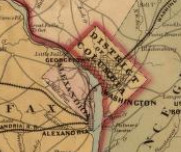

Alexandria was part of Fairfax County in 1790. Fairfax ceded land to the new federal city which was to be 100sq miles straddling the Potomac River. Alexandria then had the unique distinction of being both a part of the Federal city and Virginia.[2] The laws of Virginia were harsher towards freemen, but since Alexandria was technically in the federal city there was more leniency. With the Organic Act of 1801 Alexandrians were disenfranchised, creating further tension. It also divided the Federal District into Alexandria and Washington counties and set up a court system for both.[3] This was the beginning of Alexandria County, which eventually became both Arlington County and the City of Alexandria.

By the mid-1840s Alexandrians wanted to return to the jurisdiction of solely Virginia. At the time, Alexandria County encompassed not only the city, but also present-day Arlington County. Alexandria County was officially retroceded back to Virginia in 1847. Many Black Alexandrians moved into DC as a result. [4] Alexandria's free Black population went from 1,962 in 1840 to 1,409 in 1850. [5] In fact, Washington abolished slave trade, but not slavery within its border in 1850, which led to increased business of slave selling in Alexandria.

From 1830-50 there was not a large increase in the free Black's population, but there was an increase in clustering; the living in close quarters with others with similar situation. This is suggestive of tensions and conflict avoidance in competition for jobs with poor White residents. "The Black neighborhoods formed were on the periphery of town mostly to avoid conflict and to create a community heterogeneity of neighborhood, church, and community strength. Creating their own organizations such as churches or fraternal organizations like the Odd Fellows. Further tensions arose when Alexandria was retroceded back to Virginia." [6] Despite this, by 1850 50% of homes were Black owned in Hayti.[7]

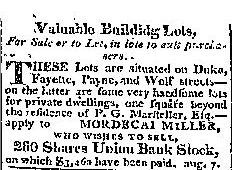

Alexandria was a thriving port. By the early 19th century there were many rich importers and exporters in residence. Some of the most prominent businessmen were Quakers. Among those the Hartshorne, Miller, Janney, and Stabler families were leaders not only in business, but in humanitarianism.

They were staunch abolitionists and fought for manumission and the fair treatment of all humans. To this end they helped enslaved people by purchasing their freedom. In a Southern city, they had to walk a fine line of following their conscience, but living and doing business with others who did not share their charitable, just thoughts. [8]

The Hartshorne and Miller families were intermarried and took a bold leap in not only building homes on land and renting to free African Americans, but went further and sold homes to freemen. The lots of land that they sold or rented were mainly in the area that became Hayti. “Robert inherited the land from his father and built additional homes, eventually selling all the homes to the free African Americans who rented them, effectively turning the block into a community of homeowners.[9] Property ownership was symbolic for many free African Americans as a way to obtain a better life, regardless of the racial tension that existed in the antebellum South. Owning land, property, and businesses gave a sense of security, better equipping free African Americans to protect their families, assert their rights in court, and gain the goodwill of White residents. When Robert Miller died, his obituary in the Alexandria Gazette read, “What he thought right that he did with his whole heart.” The homes became the foundations for the free African American neighborhood named Hayti.” [10]

[1] RONALD L. HEINEMANN et al., “ATLANTIC OUTPOST: 1607–1650,” in Old Dominion, New Commonwealth, A History of Virginia, 1607–2007 (University of Virginia Press, 2007), 18–40, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wrjzn.6.

[2] F. L. Brockett and George W. Rock, A Concise History of the City of Alexandria, Va., from 1669 to 1883, with a Directory of Reliable Business Houses in the City (Alexandria, Va.: Printed at the Gazette Book and Job office, 1883), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009797087.

[3] “Founders Online: Editorial Note: Bill to Establish a Government for the Territo …” (University of Virginia Press), accessed December 2, 2022, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0027-0001.3

[4] “District of Columbia Retrocession,” in Wikipedia, November 27, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=District_of_Columbia_retrocession&oldid=1124224094.

[5] Blomberg, Belinda .1988 Free Black Adaptive Responses to the Antebellum Urban Environment: Neighborhood Formation and Socioeconomic Stratification in Alexandria, Virginia, 1790-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, American University, Washington, DC. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

[6] “Hayti: One of Alexandria's African American Neighborhoods, Out of the Attic,” Alexandria Times, April 29, 2021.

[7] Blomberg, Belinda .1988 Free Black Adaptive Responses to the Antebellum Urban Environment: Neighborhood Formation and Socioeconomic Stratification in Alexandria, Virginia, 1790-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, American University, Washington, DC. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

[8] A. Glenn Crothers, “Quaker Merchants and Slavery in Early National Alexandria, Virginia,” Journal of the Early Republic 25, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 47–77, https://doi.org/10.1353/jer.2005.0005.

[9] The Chipstone Foundation,” accessed November 20, 2022, https://www.chipstone.org/article.php/415/Ceramics-in-America-2008/Robert-H.-Miller,-Importer:-Alexandria-and-St.-Louis.

[10] Mary Katherine Gastner, “Valuing ‘Others’: Free African American Neighborhoods in Antebellum Alexandria,” n.d